IHP+ Common monitoring and evaluation framework

Why assess interventions?

Policymakers require evidence of the likely effectiveness of the interventions they consider supporting. Once they have implemented an intervention, they need data. The data will help them understand the coverage, effectiveness and impact of the intervention and inform development of future policy.

Governments are accountable to themselves and the public for implementing policies, strategies and programmes to meet all health sector targets including Universal Health Coverage.A sound monitoring and evaluation strategy is key to accountability. Likewise, bilateral or multi-lateral donors hold recipients of their support accountable for the funds they receive. This accountability ranges from: a non-profit organization running a small-scale community intervention; through a district implementing a disease control programme; to a national government running an entire health sector.

Efficacy versus effectiveness

We distinguish between the evidence a government or organization needs to select an efficacious intervention and the data it needs to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of a chosen intervention.

We use Archie Cochrane’s interpretation:

- Efficacy indicates the extent to which an intervention does more good than harm under ideal circumstances.

- Effectiveness indicates whether an intervention does more good than harm when provided under usual circumstances of healthcare practice.

Intervention research

Researchers undertake field trials of interventions to assess their likely impact should they be implemented in other locations and on a large-scale.

Interventions may be preventive such as introducing a nutrition education programme, involve treatment such as delivering anti-retroviral treatment to HIV/AIDS patients in the community, or be health system interventions such as introducing a maternal and child health card for mothers to keep and present when they interact with a health worker.

These interventions may begin life as experiments in laboratory or clinical settings; researchers only evaluate them in field trials when their use in a community setting promises to improve the health of the targeted population. Use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs), for example, is a preventive intervention which researchers have evaluated in many contexts from the 1980s – after extensive laboratory testing.

Randomized controlled trials

Researchers design studies to obtain the highest quality evidence to answer their research question, that is they want to be highly confident that their estimates of the effect of the intervention on the outcomes are correct. They can achieve this by conducting a randomized control trial (RCT) in which they randomly assign individuals, or clusters of individuals, in the target population to the intervention or to a control group, and compare the outcome in each group.

In clinical settings, researchers randomly allocate individual patients to a group receiving a new treatment or to a group receiving the current treatment, or a placebo, and compare recovery rates between the two groups. In a field trial, researchers may allocate individuals or clusters of individuals, perhaps villages, to an intervention or a control group.

If the researchers perform the randomization appropriately, they will eliminate selection bias and the comparison groups will be similar except for the treatments received. The researchers can therefore objectively assess the effects of the treatment on the outcome and conclude whether or not the intervention had an effect on measured indicators with an associated low level of statistical uncertainty.

RCTs – known by epidemiologists as experimental designs – are difficult to manage in a field setting and so researchers sometimes use quasi-experimental studies that provide poorer quality evidence. Investigators reduce the quality of their evidence if they introduce bias into the data they collect and analyse.

Evaluating effectiveness

Some trials are successful in highly controlled environments but the coverage and impact of the same interventions can be lower when organisations scale them up or implement them elsewhere. Another problem is that some researchers are unable to convince practitioners to implement highly efficacious interventions beyond the research setting.

Implementation science

Implementation science is ‘the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services.’

Researchers and programme managers use implementation science to understand if and how they can implement an effective intervention in a specific context. They consider factors that affect implementation such as the operational practicalities of distributing ITNs, the attitudes of health workers to their mental health clients, the stigma felt by people seeking mental health care, and resource issues around setting up either intervention.

The science is about generalizing and learning from specific situations to provide insights into how to implement innovations and evaluate that process by, for example assessing typical barriers and developing solutions. The goal is ‘determining the best way to introduce innovations into a health system, or to promote their large-scale use and sustainability.’

Cost-effectiveness

Once researchers have established the effectiveness of interventions to address the same issue, they compare their relative cost-effectiveness. The health economics page of this website describes cost-effectiveness studies

Systematic reviews

The World Health Organization (WHO) issues global guidelines, or recommendations ‘that can impact upon health policies or clinical interventions’. WHO’s recommendations derive from a formal and lengthy process of consultation and literature review following the WHO Handbook for guideline development.

Central to any WHO published guidelines is a rigorous and transparent assessment of available evidence on the topic of interest, known as a systematic review. Systematic reviews systematically synthesize all known studies and draw conclusions about their combined evidence. For this reason, they provide higher level evidence even than a RCT.

GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation). The GRADE profile rates the quality of evidence provided by the paper on the basis of its design and any biases introduced during design or implementation.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement provides guidance for reporting systematic reviews. The GRADE working group website provides details of its process with software and training modules.

- The Cochrane Initiative has spearheaded systematic reviews and maintains a comprehensive database of systematic reviews in health care together with resources to undertake a systematic review.

- Other databases of systematic reviews in health include the Campbell collaboration and PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered reviews in health and social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development, where there is a health related outcome.

Monitoring and evaluation

Once an organization adopts an intervention or modifies an existing one, it needs a monitoring and evaluation plan to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in practice.

The organization may be implementing an intervention locally or on a large-scale such as rolling out a malaria control programme across a district or nationwide. The purpose of delivering any intervention must be to provide the best possible service to those who need it, and this should prescribe the design of the intervention and its monitoring and evaluation. That is, whatever the evaluation question, programme managers and evaluators must collect and explore data that identify the people who most need the intervention, and they will obtain valuable data from speaking to those people themselves.

Monitoring

Programme managers routinely collect information to monitor an on-going intervention so that they can track progress and perform oversight; it is an immediate-term process that does not consider long-term impact on intended beneficiaries.

Evaluation

Programme managers evaluate the intervention by systematically collecting information periodically before, during and after its implementation to better understand and assess the intervention. Evaluation primarily assesses effectiveness, relevance, impact, and attainment of intended results, in an effort to improve future programmatic planning or services.

Used together, monitoring and evaluation is a continuous process that assesses the progress of a project, informs implementation and decisions throughout the project cycle and future project and policy formulation. Fundamental to both are the data on which they are based; that is which data and how they are collected, managed and analysed.

Monitoring and evaluation frameworks

Managers create frameworks, or models, to frame the sequence logic to obtain the results they want to achieve and to determine the information and data they need to collect to plan, develop, implement, monitor and evaluate health programmes. They use different types of frameworks, for example: Logic Model (or theory of change), Logical Framework (or logframe) or Results Framework.

The frameworks share similar terminology and show diagrammatically how the intervention’s resources and activities are believed to achieve its intended goals and how managers will measure these results. They differ in their organization and emphasis on objectives, inputs or results and the level of information they contain. The programme development team usually chooses the type of framework but sometimes a donor prescribes its preferred framework.

Most frameworks describe the programme in terms of its inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impact, The table below shows a simple Logic Model (or Results Chain) format, and defines these terms with an example for a malaria vector control programme. Each component of the model is described by qualitative or quantitative indicators which require collection of specific data.

Input

Input indicators measure the availability of resources and can signal shortages of supplies, for example available field workers or numbers of ITNs purchased.

Activity

Activity (or process) indicators describe the services the programme provides and monitor progress, for example the number of training sessions given to field workers or workload across facilities.

Output

Output indicators describe the deliverables resulting from programme activities and monitor progress, for example number of health education sessions provided or number of ITNs supplied to households.

Outcome

Outcome indicators measure the changes in behaviour resulting from the programme’s activities and monitor and evaluate achievements, for example the percentage of population using ITNs with knowledge of why ITNs protect them.

Impact

Impact indicators measure the long-term changes in population health resulting from the programme, for example mortality rates or disease incidence.

Logic Model/Results Chain for programme monitoring and evaluation |

||||

Inputs |

Activities |

Outputs |

Outcomes |

Impact |

Financial, human and material resources, logistics, transport |

Specific actions to complete the programme |

Deliverables resulting from the activities |

Changes in behaviour resulting from the activities |

Measureable cumulative changes in health resulting from the outcomes |

Example programme to scale-up vector control |

||||

Programme funding, supplies of ITNs and sprays; trained workers etc |

Distribution of ITNs to households |

No. ITNs distributed to households |

Proportion of people sleeping under ITNs |

No. malaria cases and deaths; malaria parasite prevalence |

House spraying |

No. houses sprayed |

Proportion of people sleeping in sprayed houses |

||

A framework template usually includes the objectives, theoretical assumptions and principles of the programme. Frameworks are not only useful for planning, implementation and evaluation but they play a vital role in communication. Managers can use the model to explain to others and funders of the programme, clarifying what works under what conditions. When they discuss the model with stakeholders, they can build agreement over inputs, activities and outcomes and create ownership which will help in sustaining the programme.

Types of monitoring and evaluation

The evaluation approach depends on the timing of the evaluation in the history of the programme and the question/s asked of the evaluator/s. The table below summarizes approaches to monitor and/or evaluate the development, process, outcomes and impact of a programme. It highlights major data sources for each.

Programme staff commonly monitor the programme themselves although they may invite an external evaluator to contribute to its development (formative evaluation).

They usually appoint independent evaluators to undertake outcome and impact evaluations. Depending on the stage at which they become involved, evaluators work with the programme team to: establish the framework at the start of the programme; work with an established framework; or retrospectively create a framework when no adequate one exists.

Types of monitoring and/or evaluation and relevant data sources(Adapted from CDC) |

|||

Type of evaluation |

When useful? |

Why useful? |

Data sources |

Formative evaluation |

Development of new program; modification of existing program or adaption to new setting |

Is the program necessary, feasible and acceptable? Should and how can it be implemented? |

Review of literature and other document; analysis of administrative and secondary data; resource mapping; key informant interviews; focus group discussions; small scale surveys; |

Process evaluation and program monitoring |

When program begins and during implementation |

Is the program implemented as designed and reaching target groups? Is it within budget? Does it need any modification? |

Review of program documents including framework; analysis of administrative records; special surveys, key informant interviews; focus groups; direct observation; rapid assessments, cost analysis |

Outcome evaluation |

At end of program or implementation milestone |

How is the program impacting behaviour of targeted groups?Is it cost-effective? |

RCTs, analysis of baseline and end-line surveys and any longitudinal panel data; key informant interviews; focus groups; analysis of contextual changes; cost analysis |

Impact evaluation |

Sometime after the start of the program; at or even years after its completion |

Has the program achieved its ultimate goal of impacting the health status of the targeted groups? Informs policy and future program development |

RCTs, analysis of baseline and end-line surveys and any longitudinal panel data, and of trends in facility or CRVS data or in any parallel local surveys; key informant interviews; focus groups; analysis of contextual changes |

Design of the programme, and its framework and indicators, is central to all monitoring and evaluation activities. However, the programme team cannot anticipate all qualitative outcomes such as changes in behaviour, policies or practice arising from complex interventions.

Outcome harvesting is an approach in which ‘evaluators, grant makers, and/or programme managers and staff identify, formulate, verify, analyse and interpret ‘outcomes’ in programming contexts where relations of cause and effect are not fully understood.’ The process is well-defined with engagement of stakeholders and feedback loops to ensure that the ultimate classification and list of outcomes are verifiable and useful to potential users.

The fundamental issue for outcome and impact evaluation is whether or not evaluators can, or need to, attribute changes in coverage and behaviour (outcomes) or in health indicators (impact) to the programme. Habicht et al. classify assessments depending on the type of inference investigators intend to draw:

Adequacy assessments

Adequacy assessments investigate whether specific expected changes in indicators occurred. Evaluators use cross-sectional data and hold focus group discussions with stakeholders to examine whether the programme has achieved target values for selected indicators. They can further explore why certain targets have or have not been met. If evaluators repeat assessments over time, they can show trends towards long-term achievement of the targets. This is how governments monitor their efforts to reach the SDGs.

Probability assessments

Probability assessments investigate whether or not the programme had an effect on selected outcome or impact indicators. Using a RCT design, the programme team delivers the intervention in carefully controlled circumstances with dedicated data collection to ensure they can measure outcome and impact indicators over time. Unlike research studies, it may not be feasible or ethical to randomize the population to control groups when implementing proven interventions on a large-scale. One solution is to introduce the intervention using a randomized stepped wedge design in which the investigators maintain randomization while gradually expose control groups to the intervention until the whole population is covered.

Plausibility assessments

Plausability assessments investigate whether the programme appeared to have had an effect on the indicators over and beyond other external influences. The programme team choose from a menu of non-experimental epidemiological methods.

One approach is to identify a non-random control group and compare indicators between this group and the intervention group at the start, during and/or at the end of the programme. For example, instead of allocating villages at random to an ITN intervention, the team might identify a geographically conveniently located group of villages in which to distribute the ITNs and demarcate a neighbouring group of villages to serve as the control group.

An alternative approach would be to compare longitudinal changes in population indicators before and after the intervention without any control group. These designs can introduce considerable bias. But careful analysis of baseline, contextual, outcome and impact data within a conceptual framework can provide evidence about the plausibility of an intervention effect.

Plausibility designs require dedicated data collection and careful analysis. But when the programme is implemented on a large-scale and over many years, they also use data from health facilities and concurrent local and national surveys. Qualitative methods of collecting information are vital to understand contextual factors around implementation.

The plausibility approach is essential when a ministry has implemented an intervention to scale nationwide and over a long period.

For example Roll Back Malaria uses a plausibility framework to evaluate impact on morbidity and mortality of full-coverage malaria control in countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The framework analyses contextual data, for example on the environment, health care, households and individuals in order to determine the plausibility that malaria control activities have had impact over and above these factors. The Roll Back Malaria team used this approach in Rwanda to assess the impact of its intensified malaria control interventions between 2000 and 2010. Eckert et al. concluded that the interventions contributed to an overall impressive decline in child mortality in the country, even as socioeconomic, maternal, and child health conditions improved.

For this evaluation, the researchers drew on: data on mortality, morbidity, and contextual factors from four national Demographic and Health Surveys undertaken between 2000 and 2010; reports from the country’s health management information, community information and disease surveillance systems; climate data from the national meteorological archive; and publications of locally relevant studies.

When it is difficult to obtain data for impact indicators, investigators can model them using other available data.

For example, investigators use the AIDS Spectrum modeling package to assess the impact of interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT). Spectrum can predict the number of child HIV infections and the population-level MTCT rate using available HIV prevalence and antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage rates.

This and other models, however, rely on routinely collected surveillance data and its predictions depend on the quality of those data – WHO advises that their results be triangulated with empirical data. Hill et al. used Spectrum to compare MTCT rates across 32 countries in sub-Saharan Africa with generalize HIV epidemics and found that 50 per cent of childhood infections in 2013 were in lower-prevalence countries and recommended targeting MTCT in these countries.

Health sector performance

Most countries develop strategies and conduct reviews of the performance of their health sector.

Joint annual health sector reviews (JARs)

Joint annual health sector reviews (JARs) bring country and development partners together to assess performance and agree an improvement plan.

Because of their breadth of scope, these reviews are complex and a major task to take on.(40) They make heavy demands on data which health facility data cannot satisfy alone. They require assembly and analysis of data from additional sources, including censuses, vital registration, household surveys, administrative records and surveillance. A complication has also been that different donors required different accountability frameworks collecting different data in a single country.

The IHP+ framework

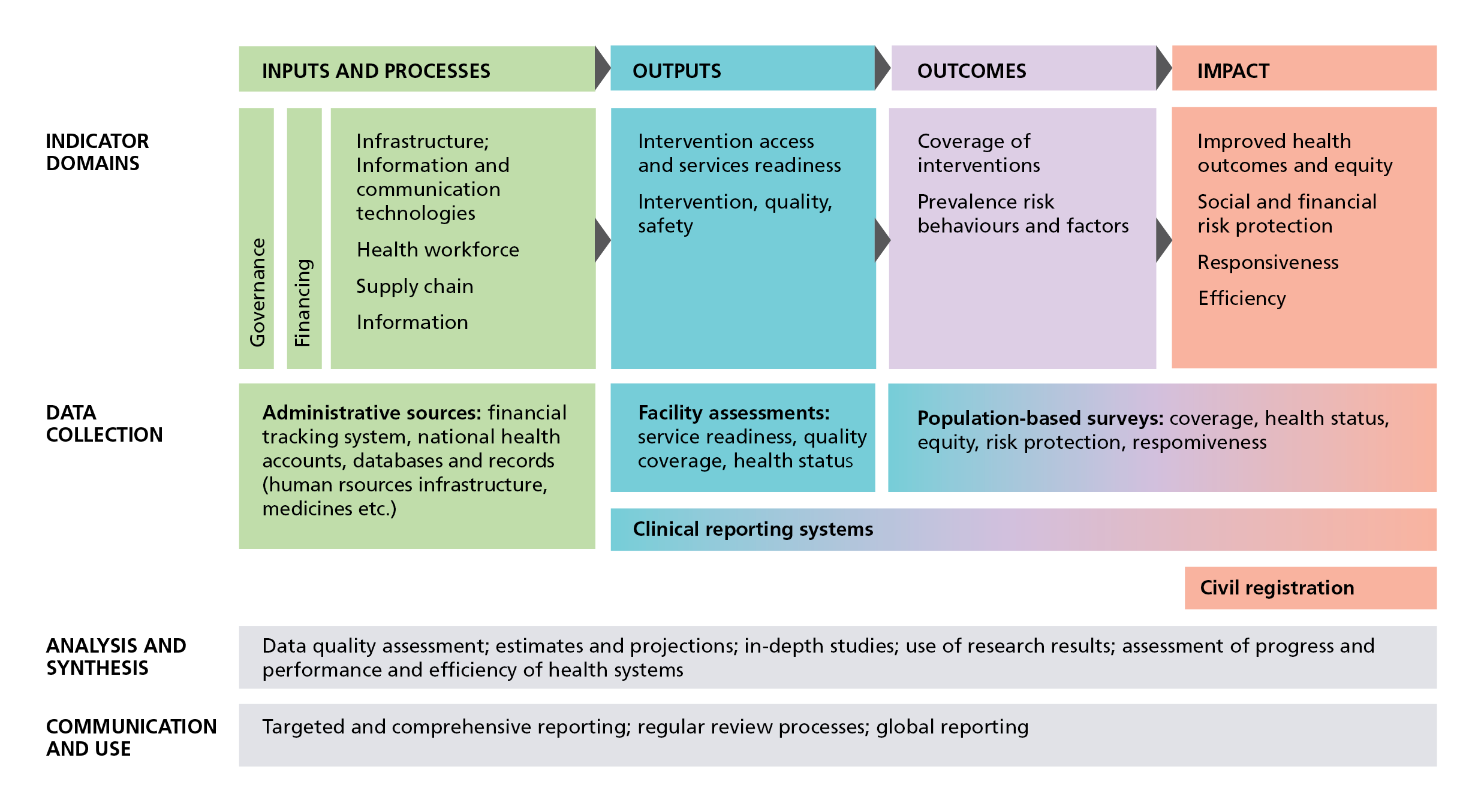

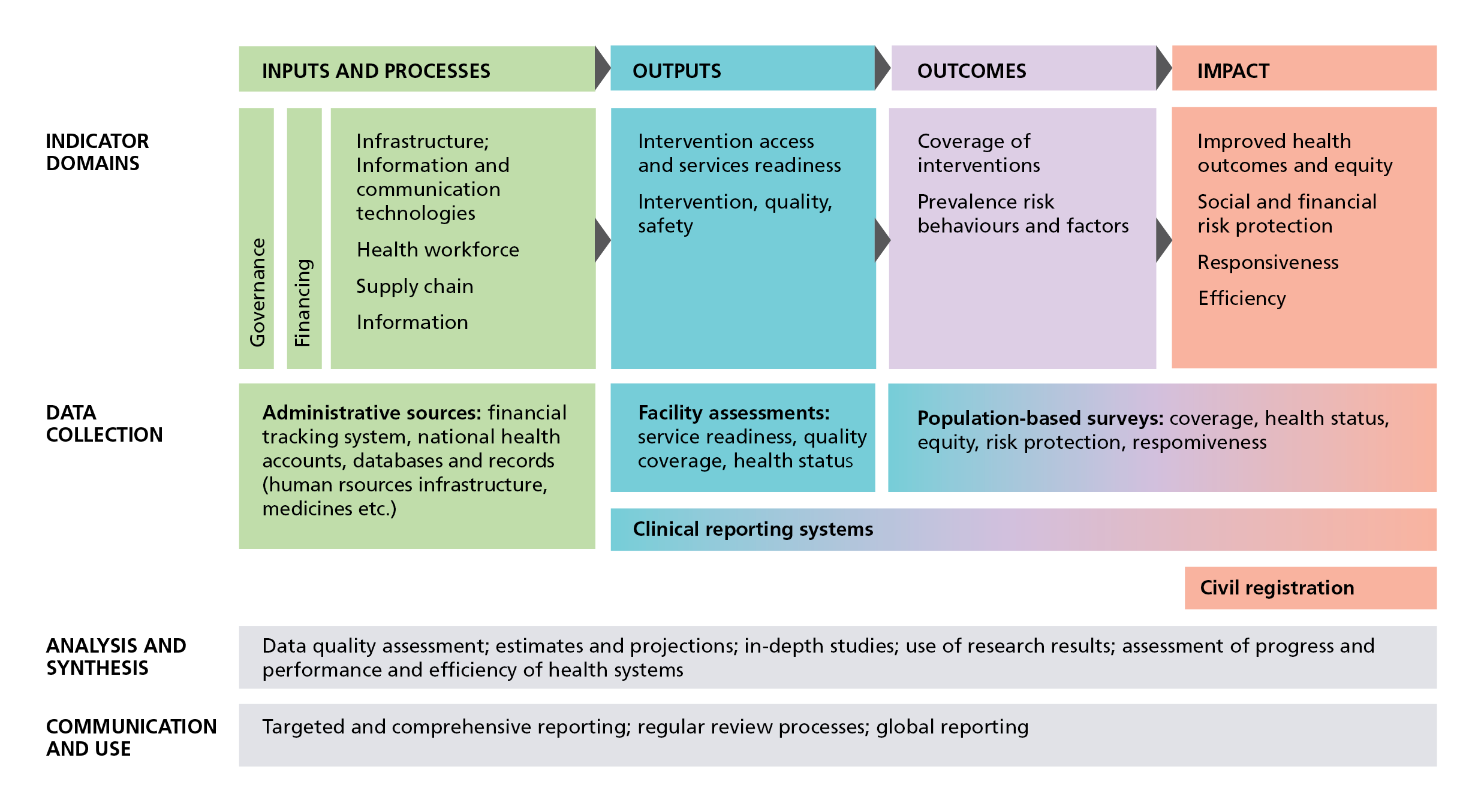

IHP+ Common monitoring and evaluation framework (World Health Organization)

In 2008, the International Health Partnership (IHP+) – of donors, governmental representatives and other organizations – proposed ‘a common framework for monitoring performance and evaluation of the scale-up for better health’ to encourage coordination across partners and strengthen country health information systems to support evidenced-informed decision-making.

The IHP+ also identified need for guidance to countries for what IHP+ calls monitoring and evaluation and review of national health plans and strategies. In 2011, the partnership published guidelines which contain what is now known as the IHP+ Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework.

The framework follows a results chain format with indicator domains across health system inputs and processes, outputs, outcomes and impact. It aligns different data sources for these indicator domains – health facilities, household surveys, censuses and vital registration records. It also indicates the types of analysis needed for decision-makers to assess levels and trends across multiple indicator domains.

WHO subsequently developed a reference list of 100 core indicators which it classifies by the same domains. The framework provides a common logic around which governments and partners can harmonize their data and reporting requirements.

The IHP+ partnership has since become the UHC 2030 partnership which has adopted the framework for its activities to support health system strengthening. The guidelines describe how to monitor, evaluate and review national health strategies.

Challenges

An evaluation framework defines the indicators to be observed during monitoring and evaluation. It is always better to use and strengthen the government health information system than to set up parallel efforts.

Evaluators must be able to disaggregate data to assess whether the intervention reaches all who need it. This means, at the very least, disaggregation of the data by residence, socio-economic status, sex and age; if the intervention is nationwide, then it will require sub-national evaluation.

The success of the intervention depends on the public’s views and how it might serve them better. The team should seek the community’s inputs at every stage of the evaluation. They can use the vital data they provide to explain the quantitative indicators they measure.

Contents

Source chapter

The complete chapter on which we based this page:

Macfarlane S.B., Lecky M.M., Adegoke O., Chuku N. (2019) Challenges in Shaping Health Programmes with Data. In: Macfarlane S., AbouZahr C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Additional resources

Field trials of health interventions: A toolbox. This open access book explains how to undertake field trials of health interventions

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Types of evaluation

WHO A common framework for monitoring performance and evaluation of the scale-up for better health 2008

World Health Organization. Monitoring, evaluation and review of national health strategies: a country-led platform for information and accountability 2011 [cited 2018 14th February]. Available from:

The Disease Control Priorities Network provides a comprehensive source of evidence-based public health interventions which network members have reviewed for their efficacy, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness.

Latest publications