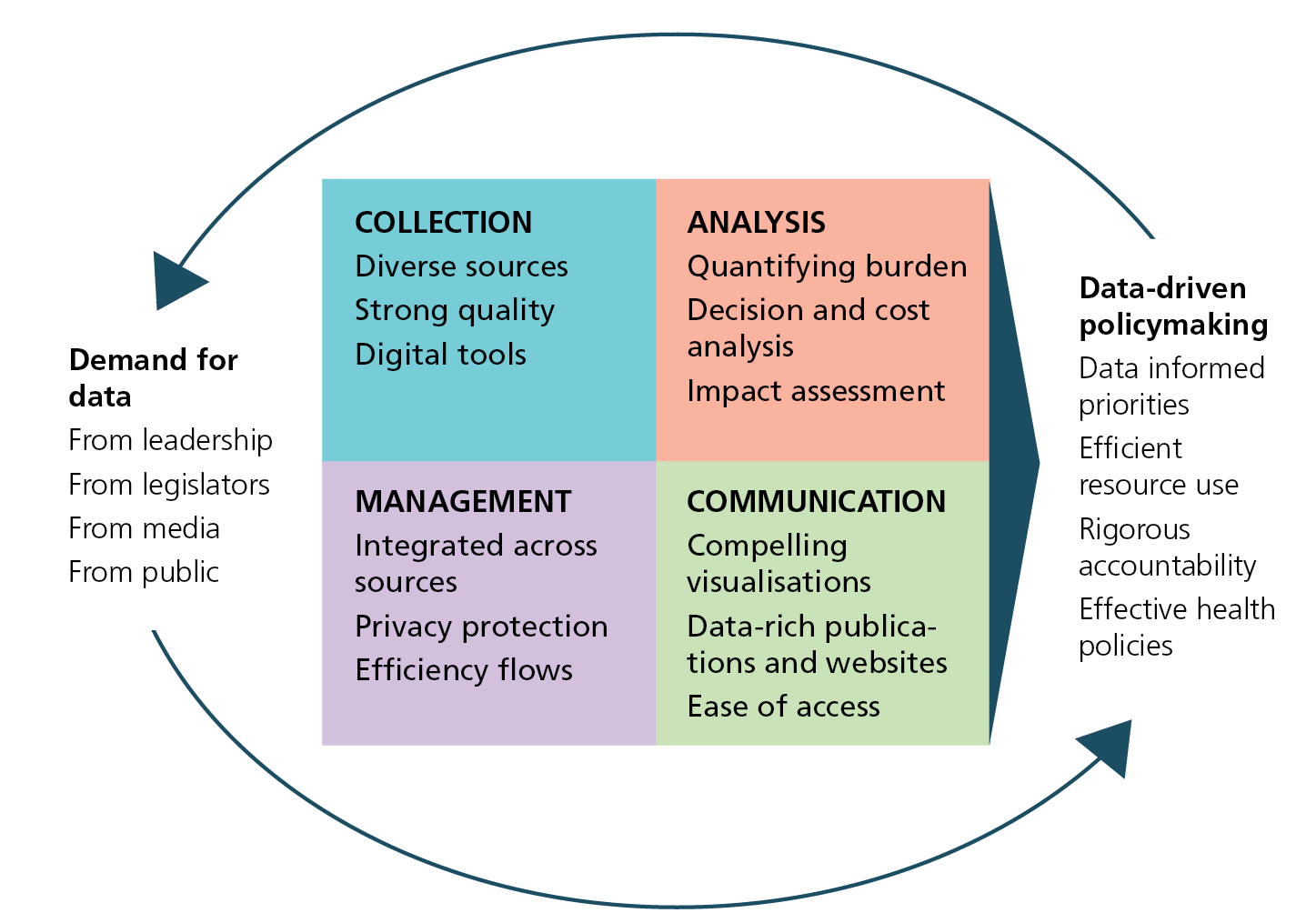

Cycle of data driven policy

Why use data to drive policy?

The policymaking function of government is powerful in creating conditions for population health. The data-driven approach levers government-generated data to produce insights, communicate information, and assess the health impact of policies and programmes.

The approach generates information that describes the magnitude and extent of a health problem to inform potential strategies to address it. Governments incorporate this information into communications to stakeholders and to the general public, and develop evaluation plans to assess the implementation and actual impact of any policy interventions implemented.

The cycle of data-driven policy

To be collected — and collected well — data must be demanded; to be demanded, data must be available.

The cycle of data-driven policy and decision-making begins and ends with a culture of demanding and using data is portrayed in the above diagram and can be summarised as follows:

- Data collection refers to the operation, scale, quality, cost, completeness, and timeliness of the surveillance and survey systems that the health agency operates, including vital statistics, behavioural surveys, health service statistics, and disease surveillance. Agencies use multiple sources from inside and outside the health system, such as census, economic, and environmental data.

- Data management refers to the system of databases and other information technology solutions necessary to house and integrate the extensive data available to public health agencies. Considerations for data management include: linking and integrating data from diverse sources; transmitting data from point of collection to point of use; making data available within the government and to external users such as researchers and the general public; and maintaining confidentiality around personal identifiers.

- Data analysis: Raw data must be cleaned, coded, and analysed to produce meaningful information. Analyses may be qualitative or quantitative and include statistical and economic modelling. Outputs of data analysis might include descriptions of health conditions or risk behaviours, health status of populations, health system functioning, or programme performance and impact.

- Data communication provides the interface between data producers and data users, including internal government decision makers, legislators, the general public, press, advocates and civil society representatives, and researchers. Communicating data to stakeholders serves many purposes: providing information; explaining priorities; defending resource allocation and policy choices; and establishing and conveying accountability to goals and benchmarks. Data should be disseminated in multiple forms: discrete responses to specific queries; print or online reports on health issues or population health status; performance reviews and indicator tracking; policy briefs; part of press releases, speeches, and testimonies; and in budget and legislative proposals.

This data use cycle is enabled by an institutional culture that encompasses internal and external operations, stakeholder expectations, and organizational values around using data. Often, data producers do not receive feedback around how data they provided have been used – who, how, and where the data were used, how they were received, and whether there were quality or other technical problems. Proper feedback increases incentives and motivation for data producers to improve data collection systems. Similarly, creative and accessible analytic outputs and data visualizations provide options for decision makers to integrate data throughout their activities.

Practices to improve data use

We describe a set of practices that government public health agencies can adopt to optimize the data-driven policymaking cycle. We have synthesised these practices from several sources and base them on our professional experience. The practices are not exhaustive and are intentionally succinct. We have chosen those we think contribute most to identifying population health challenges, developing cost-effective interventions, and communicating these priorities to stakeholders.

We organize the practices into three broad categories:

MEASURE: to improve data use

The need for sound measurement of the dimensions of a health challenge seems obvious. Yet experience shows that the absence of measurement strategies often thwarts effective public health action especially at local levels where health decisions are often made. We suggest some measurement strategies for public health agencies:

Select indicators with measurable targets

Public health agencies should specify indicators that describe the needs and priorities of populations, including their utilization of the health system, and inform interventions and policies to address them. Indicators span metrics of health status, health risk behaviours and exposures, and health service utilisation. Indicators should aim for ambitious, achievable and measurable targets and where possible conform to international standards, such as those in the WHO 100 Global Reference List of Core Health Indicators.

Translate risk factors into attributable mortality

Health outcome data alone, such as cause-specific mortality or disease prevalence rates, provide only limited information to plan interventions. As non-communicable diseases continue to increase, public health agencies need to measure the contributions that determinants and behaviours make to the health burden. Risk factors include, for example: tobacco and alcohol use, poor nutrition, and physical inactivity, as well as toxic exposures, such as poor air quality; and social factors, such as poverty and discrimination. Quantifying these factors makes it possible to rank and estimate the cost-effectiveness of potential interventions.

Of particular interest from a policy perspective is the proportion of the disease burden in a population that public health practitioners could alleviate if they reduced or eliminated the effects of specific causal or risk factors. There are several epidemiological techniques for translating risk factor data into health outcomes. The most common is to calculate population attributable fractions (PAFs).

Disaggregate reported data

Public health agencies must stratify their data into relevant subgroups. Restricting analysis to averages obscures differences across subpopulations and can result in resource misallocation and persistent health inequalities. Categories of stratification should be standardized and applied to all data sources systematically. Key stratifiers include age, sex, subnational (or sub-urban) geography, education, occupation and household wealth.

Identify vulnerable populations

A fundamental mission of public health agencies is to identify and address differences in health between groups and identify and assist vulnerable populations. The first step is to describe health inequalities and relate them to the social and environmental factors that drive them. There are many ways to analyse and present data on health inequalities. At a minimum, it is useful to compare rates and rate ratios by sub-populations. Specific inequality metrics can quantify the differences in health burden, by comparing and visualizing excess mortality by sub-group or examining socio-economic inequalities in a health outcome. Two inequality metrics are the relative index of inequality, or the concentration index.

INFORM: to improve data use

This group of practices focuses on how governments communicate their priorities to stakeholders to build support and hold themselves accountable. They include practices around sharing of data.

Publish data driven reports communications

All public health agencies should publish up-to-date data reports to inform the public about health issues and priorities. Data reports communicate progress on quantitative indicators to demonstrate accountability and build support for new policy and programmatic proposals. Reports can cover specific health issues (such as diabetes, tobacco use, or malaria), the health status of important subpopulations (such as the elderly, youth, children, poor, or living with disability), or of populations in specific neighbourhoods or districts. Communications departments should incorporate data routinely into press releases, testimony, speeches, annual reports, and other public communication materials. Desirable characteristics of data reports include:

- Published as a series, with regular production; available in print and online.

- Each report focuses on a single key topic of public health priority.

- Short (~4 pages) with effective use of graphic design, and compelling data visualizations.

- Integrate multiple data sources (mortality, health services, surveillance, etc.).

- Incorporate explicit discussion about policy and programmatic implications and responses to the data.

- Released with a well-considered communications/dissemination plan to press and stakeholders.

Share data sets with external users

Public health agencies should develop policies and procedures for releasing data to eligible stakeholders. It is critical that they do this within supportive legal and administrative frameworks, following agreed standards for confidentiality and data security. This can include sharing of individual record information as part of public health surveillance. Agencies should remove all individual identifiers from data sets before sharing with external researchers. It is essential to guard against the risks of individual identification when providing detailed data for small geographic areas or population groups. Reporting small cell sizes in an epidemiologic report, even without identifiers, can provide sufficient information to match with another dataset that contains identifiers. The growing open data movement promotes a move away from This implies that data release files are structured and non-proprietary so that potential users can extract maximum value from data.

Document metadata and data cleaning practices

All empirical data sets are imperfect in some way and need to be adjusted, or cleaned, to maximise their utility. Necessary cleaning, coding, and grouping of data should be well documented in a detailed data dictionary and analytic notes/guidance (or metadata). This can include creating new variables (e.g., a ‘poverty’ variable based on annual income); grouping variables (e.g., ages or dates); or assigning International Classification of Disease codes to diagnoses.

BUILD: improve data use

We refer here to building institutional processes and structures that promote exemplary data use. This entails investment in human resources, workforce capacity-building, and potentially, organizational restructuring.

Make data available for leadership review

Management needs for information range from a minister or other leader needing readily available information on key initiatives and indicators, to an emergency manager needing rapid updates on a public health crisis, to program directors reviewing reports during a formal process of performance monitoring and programme review.

Leadership should establish processes and use tools that leverage data to facilitate its use. Processes include routine compilation, analysis, and presentation of data to managers and leaders, for oversight and performance monitoring and for strategic review and planning. This should occur in both in a high-frequency (daily, weekly, monthly) and distilled manner, as well as more expansive and discursive forums requiring more preparation (e.g., quarterly or annual health sector reviews).

Customized dashboards are useful in conveying information to managers and leaders – using simple visualizations. Data analysts should construct dashboards taking into account the needs of intended users, availability and quality of data sources, and the overall management process into which the dashboard will fit.

Build a specialized data unit

Policymaking is a complicated process that requires inputs from a variety of sources and perspectives. For example, the formulation of a plan to increase tobacco taxes has public health as well as economic implications and requires data from public health, finance, and law enforcement sources. This needs to integrate wide-ranging information for policy development and should be supported by data management and analytic capacity. Moreover, assuring best data use practices across a complex organization requires substantial brokering among technical and nontechnical stakeholders to share data and agree upon interpretation and communication of findings. Public health agencies can establish central units to serve these cross-cutting needs.

Sometimes referred to as public health observatories, such units should have the following responsibilities:

- Compile and link agency datasets; identify and obtain access to external datasets.

- Perform advanced epidemiologic and economic analyses.

- Develop and disseminate reports and reviews.

- Establish policies and standards for management, sharing, analysis, and presentation of data across the agency; and develop, define, revise, and report core indicators.

- Respond to requests from leadership for policy analysis, economic analysis, and impact estimation.

- Provide guidance and training to technical staff across the organization and at other levels of government.

- Liaise with external partners, such as universities and public health institutes.

Build capacity for quality and transparency

Data quality limitations should rarely be an absolute impediment to data use. In most cases, with appropriate caveats and transparency about data limitations, even lower-quality data can provide actionable and valid insights. Data analysts and practitioners should apply some simple rules when deciding whether to use or to release data. Does examining this data set bring observers closer to the truth or further from the truth? Is this decision better-made or is the public better-informed if the data set is not used and not released? In the vast majority of cases, the answers will lead toward more use and more transparency.

Build analytic skills across departments and levels

Though specialized units are essential, agencies should also build and maintain strong analytic capacity throughout programmatic departments. Agencies should strive to create a community of practice among data producers from across the organization in which they share information, agree on standard practices, access new skills and learn new methods, etc. Such distributed capacity should also be fostered between the national and subnational level. Providing tools and training and promoting a culture of data use at the local level should be priorities for central agencies.

Extending a data component to all public health functions relies on the skills and capacities of health sector workers, who are often overloaded, who necessarily prioritise care functions over data collection, and who may lack technical expertise, including in information technologies. On the other hand, such skills are often available in academic institutions and among health personnel involved in research studies. Leveraging capacities in academia can help develop the skills of government staff.

Build alliances for change

New technologies in health data collection and management are generating vast quantities of information from multiple sources, including non-traditional sources such as social media and genomic analyses. There is potential for accidental or deliberate misuse of such data and risks of public hostility to sharing of data that could impede their use for improved public health. Open dialogue about the purposes and use of data collection – especially about data derived from clinical and other individual records – should be part of a national data use strategy. As emphasised by the American Health Information Management Association, discussions on ethics, informed consent, privacy, confidentiality, intellectual property, and commercial uses of data collected by public institutions should involve not only technical experts, researchers, and public and private health institutions, commercial entities, but also, critically, the public.

Contents

Source chapter

The complete chapter on which we based this page:

Karpati A., Ellis J. (2019) Measure, Inform, Build: Enabling Data-Driven Government Policymaking. In: Macfarlane S., AbouZahr C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Additional resources

Self-assessment tool for the evaluation of essential public health operations in the World Health Organization European Region. This tool is designed to guide a broad self-assessment of all public health operations within Member States in the WHO European Region.

Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization developed this handbook to provide an overview for health inequality monitoring within low- and middle-income countries, and act as a resource for those involved in spearheading, improving or sustaining monitoring systems.

Monitoring subnational regional inequalities in health: measurement approaches and challenges. Hosseinpoor et al describe, compare and contrast current methods of measuring subnational regional inequality.

Standards to facilitate data sharing and use of surveillance data for public health action. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prepared these standards to ensure the security, confidentiality, and appropriate use, including sharing, of data.

Guide to the establishment of health observatories. This guide developed by the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. is intended for countries wishing to develop their own National Health Observatories.

Providing health intelligence to meet local needs: a practical guide to serving local and urban communities through public health observatories. The World Health Organization Kobe Centre wrote this to guide academia, civil society organizations and individuals who are planning, developing or sustaining a public health observatory designed to provide information and intelligence on local and urban populations.

From data to policy: Good practices and cautionary tales. AbouZahr, Adjei and Kanchanachitra examine the relation between health statistics and policymaking at country and global levels. Read more