Data about the health workforce

There are serious shortages of health workers worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). International organizations have issued resolutions and frameworks positioning human resources for health (HRH) at the centre of the global health agenda and calling for efforts to strengthen the health workforce. Few of these resolutions address the challenges of providing decision makers with sufficient information and evidence to build a ‘fit for purpose and a fit for practice health workforce’, able to respond to the health needs of the people they serve.

There are significant gaps in availability and quality of data describing the health workforce, and little consistency between countries in how they monitor and evaluate HRH strategies. Few LMICs can provide regular accurate data on the size and distribution for the five main categories of health workforce, namely physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists and pharmacists.

Increased mobility patterns, and complex flows in and out of the health workforce need to be monitored and taken into account in planning the health workforce as well as in the development of new policies and strategies. Reliable HRH data are essential to respond to these challenges.

HRH indicators and their data sources

The World Health Report 2006 defined HRH as ‘the stock of all individuals engaged in the promotion, protection or improvement of the health of the population’. Strictly speaking, HRH include unpaid caregivers and volunteers who contribute to improvement of health but data are generally limited to people engaged in paid activities.

Operationally, there is no single measure of a health workforce but it is useful to categorize health workers by three elements:

- Their training (health and non-health).

- Their current occupation (tasks and duties performed in the job).

- The industry in which they work (activities of the establishment or enterprise).

Indicators

National and global stakeholders use indicators originating from multiple sources to describe, manage and forecast the health workforce situation depending on the context. But even in national settings where the quantity and quality of HRH information are adequate, managers rarely establish specific HRH targets and indicators let alone track them in national health systems policies, strategies and development frameworks. We describe some of the indicators that the international community has recommended for countries to use.

Two of WHO’s Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators refer to the health workforce, in terms of supply (flows) and availability (stock):

- The production of health workers (flows): the number of graduates from health workforce educational institutions (including schools of dentistry, medicine, midwifery, nursing, pharmacy) during the last academic year per 1000 population which WHO recommends be obtained from training school databases.

- The availability and distribution of health workers (stock): health worker density (by cadre) and distribution per 1000 population which WHO recommends be based on data from national databases or health workforce registries. Health worker density and distribution is also the indicator for SDG target 3c.

National Health Workforce Accounts

In May 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health (GSHRH): Workforce 2030 and proposed the development of National Health Workforce Accounts (NHWA) to: ‘create a harmonized, integrated approach for annual and timely collection of health workforce information, improve the information architecture and interoperability, and define core indicators in support of strategic workforce planning and global monitoring.’

NHWA include 78 indicators each falling into one of ten modules grouped into categories that correspond with the data required to develop policies to achieve ‘UHC with safe, effective person-centred health services’.

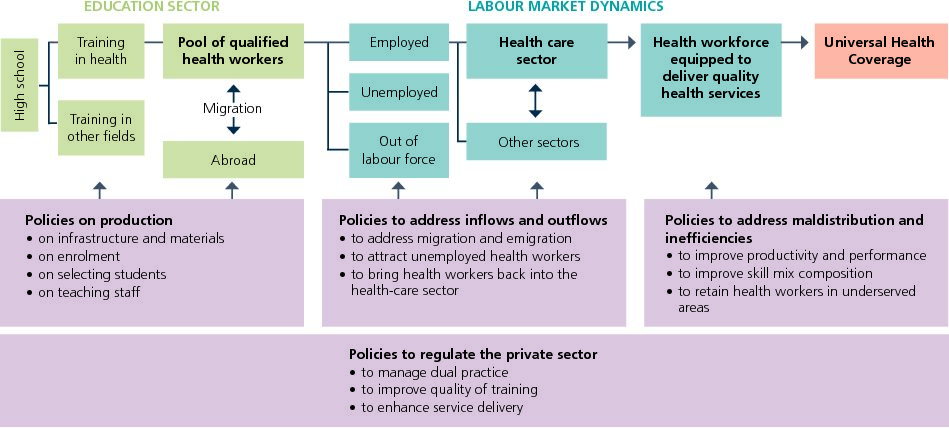

The Health Labour Market (HLM) framework developed for delivery of Universal Health Coverage and shows the labour dynamics that require measurement in relation to four policies.

Health Labour Market (HLM) framework. Source: World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health workforce 2030.

To measure and operationalize the HLM framework, the NHWA indicators are structured around 10 modules, each of which address specific policy questions in the framework. These include indicators for developing and monitoring:

- Policies that aim to steer the production of health workers.

- Policies to address health labour market dynamics.

- Policies to address the maldistribution and inefficiencies of health workers.

- Policies related to the private sector, governance and regulation of HRH.

Indicators for each of the 10 modules can be found in the NHWA Handbook which provides metadata for each indicator suggesting its ideal source and method of measurement.

The WHO and the Global Health Workforce Network propose that measurement of a fit- for-purpose and a fit-for-practice health workforce (what the HLM framework calls a ‘health workforce equipped to deliver quality health service’) involves four core dimensions, that is:

- Health workers are available.

- Health workers are physically and financially accessible.

- Health workers are culturally and socially acceptable to the population.

- Health workers are enabled to provide high quality care to all those in need.

The NHWA contains indicators that measure all these dimensions but none that specifically address quality of care, nor does it include qualitative indicators of acceptability of the services to the population.

Data sources

No single source or provider can supply the data for the range of NHWA indicators. The NHWA data source landscape requires a multi-stakeholder inter-sectoral approach, involving national statistical offices, ministries of health, finance, labour, education and immigration, and also professional associations or councils and communities. Health workforce data are produced by five major sources: national population censuses, labour force and employment surveys, health facility assessments, routine administrative information systems and health professional association’s records or registries. We describe each source below and provide a a comparison of their attributes in the table.

Population-based sources:

- Population censuses: most countries undertake a cross-sectional national census every five to ten years to enumerate and describe their total population at that time. If the census contains questions on occupation, planners can use the data to map the distribution of the health workforce by cadre, disaggregated by age and:sex for census enumeration neighbourhoods. Censuses usually have high coverage and produce high quality data.

- Labour force surveys: are regular cross-sectional national sample surveys of households designed to obtain employment data. These surveys enquire about occupation and delve into greater detail than census on, for example, place of work, industrial sector, remuneration, time worked and secondary employment. Frequency varies by country from every month to every five years. The sampling process and sample size limitations can preclude detailed data disaggregation.

- Health facility assessments (HFAs): there are many forms of health facility assessment but they usually involve a complete inventory of facility activities and resources. HFAs may cover all facilities or a sample of facilities and occur at different time intervals. They only provide data for individuals working in the facility (including those with non-health field training) but they can be disaggregated by faculty type, geographical area and staff age and sex. HFAs may collect data on salaries, in-service training, provider productivity, absenteeism, supervision and available skills for specific interventions.

Institution-based resources:

- Administrative sources: these include records of public sector employees with details of professional training, registration and licensure. These data are maintained longitudinally for each employee and are usually accurate and up-to-date. They can be disaggregated by staff demographics, job title, salary and place of work. These records do not include people working in the private sector and suffer from double counting and ghost workers.

- Training institution and professional association databases: these include records and registries kept by school or university administrations on education and training, or by council boards on memberships. These databases provide a good basis for estimation of numbers and densities but in many countries they are not regularly updated; this challenges their quality and completeness especially when registration is not compulsory.

Analytical attributes of human resources for health data sources

Attribute |

Population-based sources |

Institution-based sources |

|||

Census |

Labour forcesurveys |

Health facilitysurveys |

Admin sources |

Training databases |

|

Complete count of health workforce |

*** |

*** |

** |

** |

** |

Across sectors coverage (public, private) |

*** |

*** |

* |

** |

** |

Disaggregated data (age, sex, geography) |

*** |

** |

** |

** |

* |

Capturing unemployment |

* |

*** |

– |

* |

– |

Rigorous data collection / management |

*** |

*** |

*** |

** |

* |

Periodicity |

* |

** |

** |

** |

** |

Occupational data coding |

* |

** |

** |

** |

** |

Sampling errors |

*** |

** |

* |

** |

** |

Tracking of workforce labour market entry/exit |

* |

** |

– |

** |

– |

Tracking of in-service training / productivity |

– |

– |

*** |

* |

– |

Accessibility to micro-data |

** |

*** |

*** |

** |

* |

Relative cost |

* |

*** |

*** |

** |

** |

Key: *** Most favourable; ** Moderate; * Least favourable; – Not available |

|||||

Human resources information systems

Because HRH data derive from so many sources and reach across sectors, it is essential that human resource planners establish a centralized database, or at least a series of interoperable databases, so that they can analyse the national workforce situation, monitor trends and report indicators internationally. Health management information systems have not been successful in generating adequate HRH data and so human resource managers maintain information systems dedicated to human resources. A HRH information systems (HRIS) is a ‘systematic procedure to acquire, store, manipulate, analyse, retrieve and distribute pertinent information regarding the health workforce’. This specialised system is part of the broader complex of systems that make up a country’s health information system.

HRIS provide a structure for collecting data, assessing their quality and analysing them to produce information on the size, distribution, composition, skill mix, productivity and performance of health workers. The systems are vital in supporting countries to develop, monitor and evaluate their health workforce.

For example, a decade after Kenya established its HRIS – the Kenya Health Worker Information System (KHWIS) – in 2002, research demonstrated improvements in health worker regulation, human resources management, and workforce policy and planning at the ministries of health. ‘This real time information helps decision making; we can query the existing numbers of nurses, their training and their current place of work.’ senior officials said.

The main goal of a HRIS is to provide national and sub-national health decision makers with useful and up-to-date information that can inform and support policy-making, and development, management, and planning of HRH. To do this, a HRIS draws on a complex system of inter-sectoral sources of data including labour workforce statistics, education inputs, outputs and trajectories, supply and demand balances operating at national and/or at sub- national levels.

The HRIS should cover most of the 78 NHWA indicators. These include workforce production, vacancy and recruitment, finance, registration, benefits, payroll, migration, performance management, training, and retirement. A health workforce registry and HRH observatories are also central to the system. The HRIS will evolve in response to the development of the NHWA. NHWA will encourage a standardised approach to data management that supports comparability and inter-operability.

A HRIS is typically a computerised structure – run at national and sub-national levels. It relies on sophisticated software for entering and updating data, databases for storage and tools for analysis and reporting. A digital and linked system improves the availability of real-time HRH data, enhances its accuracy, provides access to aggregated and disaggregated data, and regular analysis and reporting; and increases the system’s ability to track people and their mobility.

Development of the HRIS is a lengthy stepwise process that engages the key people who supply and use HRH information. The CapacityPlus project has published guidelines and resources for building, maintaining, evaluating and improving the HRIS. They suggest the following five step process to strengthen the HRIS:

- Build HRIS leadership: a multi-sectoral multi-stakeholder’s leadership group can initiate, lead and monitor all HRIS activities, and agree policy decisions the HRIS will inform.

- Assess and improve existing systems: analyse existing HRIS capabilities and requirements of the ministries, councils and organizations that will use the new HRIS solution.

- Develop the system: identify the functions the system will perform and develop a system that include the functions that matter and are accessible and acceptable to users.

- Use the data to make decisions: ensure the right leaders have easy and timely access to analyses and reports, and that they use this evidence to inform management and planning.

- Ensure sustainability: develop monitoring and evaluation tools to assess the system’s performance, with measurable indicators. Ensure the integration and interoperability of the HRIS with other information systems.

Analysis, presentation, interpretation

The analysis of human resource data presents similar challenges to the analysis of other health data. Firstly, it is essential that data analysts assess the quality, completeness and consistency of available data. Quality HRH data should be reliable, efficient to collect, frequently updated, inclusive across cadres and settings, and supported by interoperable, open-source information systems.

If the HRIS is computerized, key quality checks can be automated as can the calculation of the indicators, categorized by, for example: distribution of density of health workers by cadre, sex, age, administrative area, and over time; and migration rates by cadre, sex, age and receiving country over time.

Visualization of the data using figures and maps help managers and policymakers see trends and inequities, for example, across urban and rural areas. Managers should be familiar with the details of the data system and use the regular reports produced by the system but also, where necessary, analysts should caution policymakers about the interpretation of the indicators they receive.

The analyses depend on the policy questions that need to be answered to inform decision making and also on the methodology that is most appropriate to answer them. Some tailor-made tools, such as the Workload Indicators of Staffing Needs (WISN) are available to analyze HRH data for specific planning purposes.

Because the sources of data relevant to HRH are quite diverse, some countries use mathematical modelling of health workforce data to develop estimates and inform HRH plans. Modelling may be needs-based (focussing on the need for health services), supply-based (focusing on the production and inflows of health workers), demand-based (estimating future health service utilisation) or a combination of these approaches.

A recent literature review conducted to understand how, which and where different HRH metrics are available showed that it is high-income countries that most use the more sophisticated statistical analysis.

Planners and researchers have made limited use of qualitative methods to describe the HRH situation. Understanding motivations, for example around migration, requires a mix of quantitative and qualitative information. With the involvement of multiple stakeholders – including communities and patient groups – use of mobile technologies and analyses of social media big data provide opportunities to improve both quantitative and qualitative evidence on HRH.

Measuring migration and mobility

Migratory patterns of health workers are also growing increasingly complex and are not limited to movement within and to OECD countries. WHO member states adopted the Global Code of Practice in the International Recruitment of Health Personnel in 2010 which promotes ethical international recruitment of health personnel and encourages the exchange of information about migration, as well as, reporting every three years on measures taken to implement the Code under a National Reporting Instrument.

As of 2016, there have been some improvement in the efforts of countries to implement the Code, but the full potential of data on mobility of health workers has not yet been achieved. Evidence to date points to substantial intra-regional, South-South, and North-South movements and these need to be better quantified to complement the better understood movements from the Global South to the Global North. Temporary migration, including professional registration and employment in multiple jurisdictions, is also increasing in prominence.

Emigration is difficult to measure given the complexity of health worker mobility patterns. Better measurement of immigration across all countries and reporting through the 3rd Round of reporting of the WHO Global Code and implementation of NHWA will enable a fuller understanding of health worker migratory patterns. The linking of data held by professional councils and public employers, as evidenced in Ireland, also provides a more comprehensive picture of the health labour market and mobility.

HRH observatories

Observatories are important in coordinating HRH data to inform policy. Since their inception in Brazil in 1999, national and regional HRH observatories have emerged in different parts of the world. They collect and analyse health workforce data and advocate for the use of the best evidence for the development and management of the workforce.

At a global level, the WHO Global Health Workforce Statistics, within the Global Health Observatory Data Repository, collects and compiles cross-national comparable data on the health workforce for all 194 Member states. The GHO utilises publically available data from official publication and research papers.

The counts and densities included in the Global Health Observatory, can be considered the best currently available snapshot of global health workforce availability. WHO used thresholds to permit cross-country comparisons. However, there is an ongoing debate as to whether those are planning targets that a country should or must achieve or soft measures of global monitoring.

Challenges and opportunities

Countries and the international community have made outstanding progress in strengthening HRH since the 2006 World Health Report drew attention to the health workforce crisis. HRH planners are producing more information and are assisted by several international initiatives to collate and use data from multiple sources; the development of HRIS and the creation of HRH observatories are successful examples. However, lack of standardised approaches, specific data collection tools and data comparability limit or compromise the availability of HRH information.

Data collection methods and systems have evolved significantly over the last decade. But persistent gaps remain, making it difficult to prepare appropriate planning models and develop evidence-based policies and programmes.

The NHWA are an opportunity to scale-up standardised approaches to data collection. By using well-established processes and tools such as the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), NHWA improve comparability, and interoperability of multiple data systems. Well implemented, the NHWA, in particular its online platform, could be the best source of HRH information and facilitate inter-agency, inter-country and intra-country data exchange. Information could be linked to health outcomes to inform policies and decision making about the health workforce.

Alongside tools and guidelines, implementation of the NHWA, requires a comprehensive approach to capacity building to support HRH planners in understanding, contextualizing and implementing the NHWA and reporting up-to-date data to WHO.

The HLM framework and the mobility patterns of the health workforce set the basis for identification of priorities and definition of essential data and indicators. The NHWA take this framework into account as well as aiming for standardization, comparison and inter-operability of information.

The NHWA are a remarkable step toward the improvement of essential data for planning and evidence based decisions. Implementation of NHWA will benefit of an increasing connected health workforce in counts and competencies and the rapid technological development. Sustained implementation of NHWA will depend on country ownership and particularly, the capacity of national stakeholders to collaborate and share information and knowledge emerging from existing fragmented HRH data systems.

Contents

Source chapter

The complete chapter on which we based this page:

Siyam A., Diallo K., Lopes S., Campbell J. (2019) Data to Monitor and Manage the Health Workforce. In: Macfarlane S., AbouZahr C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Additional resources

The National Health Workforce Accounts portal is a system by which countries progressively improve the availability, quality, and use of data on health workforce through monitoring of a set of indicators to support achievement of Universal Health Coverage, Sustainable Development Goals and other health objectives.

World Health Organization Global health workforce statistics.

Global Health Workforce Network. Data and evidence hub.

World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030.

World health Organization. The State of the World Nursing Report 2020.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2006: working together for health.

World Health Organization. Report of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth: Working for health and growth: investing in the health workforce.

World Health Organization. Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health: with special applications for low- and middle-income countries.

World Health Organization. Minimum Data Set for Health Workforce Registry. Human Resources for Health Information System.

World Health Organization. Guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes

World Health Organization. Delivered by Women, led by Men: the gender gap analysis. A Gender and Equity Analysis of the Global Health and Social Workforce Human Resources for Health Observer